About

the artist

Biography

(Excerpt, read more below: “More about Studio SA/JO”)

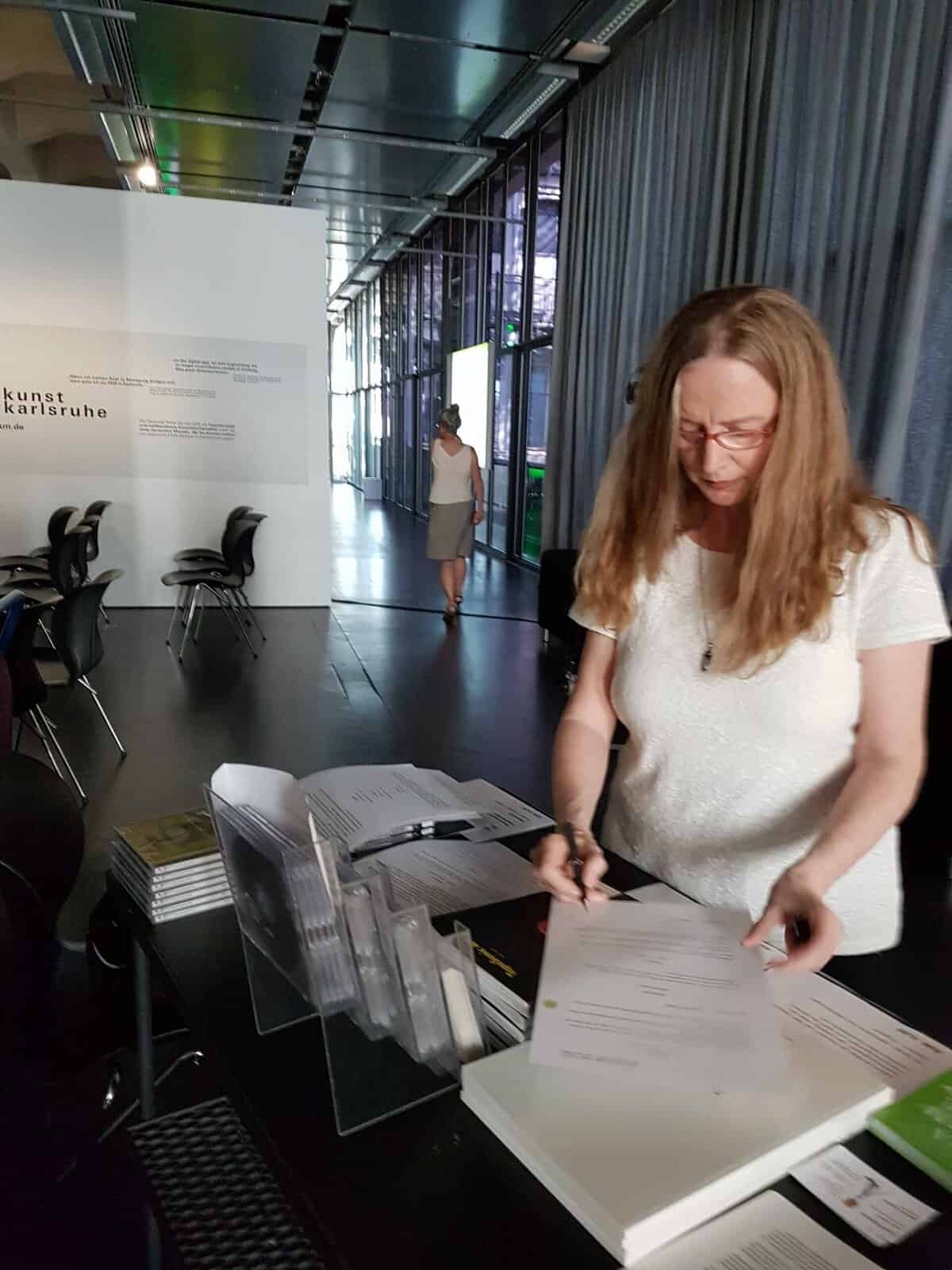

Sabine Schäfer, 2019,

Photo: Anna-Maria Letsch

|

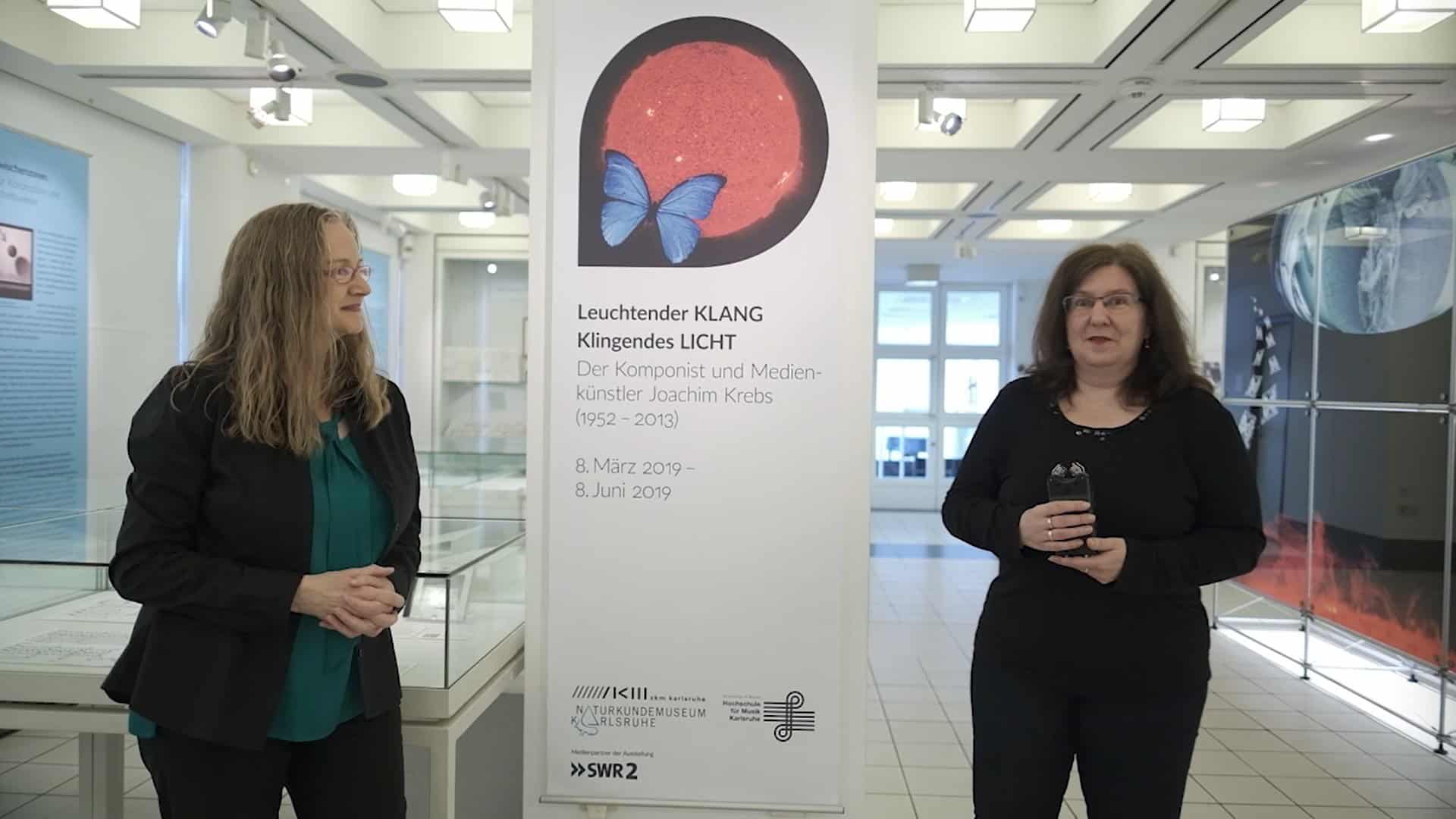

SABINE SCHÄFER 1957 born in Karlsruhe, Germany. Lives and works as media artist and composer in Karlsruhe. From 1997-2013, acting as artist-couple, together with Joachim Krebs. Since 2014, beyond the veil of Joachim Krebs, the Studio <SA/JO> is continued by Sabine Schäfer |

ARTISTIC PRODUCTION Since 2017, Development of interactive grafic reproductions with Audio QR Codes |

VOLUNTEERISM Since 2018 Member of the board of the Section Media Art and Photography of the GEDOK Karlsruhe

|

|

PUBLICATIONS ON THE ARTISTIC WORK (selection) 2008 2007 2003 1994/2007 |

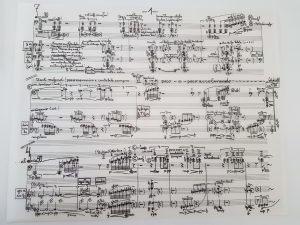

ARTISTIC DEVELOPMENTS / RESEARCH 2017 2015 1993–1996 1991–1996 1991 1990–1992 1991 TopoPhonien II: first 16-channel, concert sound space installation 1992 Construction of the 24-channel system “Topoph24” for spatial sound control 1992„TopoPhonicZones“: first 16- and 23-channel, enterable sound space bodies 1994/95 Development of a keyboard-controlled MIDI interface for spatial sound control 1999 Till 2002 TopoPhonien – common information: 1989–1992 1988–1989 1988–1989 |

EDUCATION / TEACHING Studied piano and composition at the University of Music Karlsruhe: composition with Mathias Spahlinger and Wolfgang Rihm / master’s degree in 1992, improvisation “Gruppe Kreative Musik” with Eugen Werner Velte, piano with Günter Reinhold 1989 1987/88 1989–2024 2015

|

|

ARTISTIC WORK AS A COMPOSER-PERFORMER 1987/88 „ULUDAG“ Art-Rock-Projekt u. a. mit Werner Cee (b) und Peter Hollinger (dr) 1984-1991 Gründung der polymedialen Gruppe PANTA RHEI gemeinsam mit dem Komponisten und Violinisten Helmut Bieler-Wendt; zahlreiche Vernissagen-Auftritte, Konzerte sowie die Entwicklung von interdisziplinären Projekten 1983-1986 Konzerte und Performances der Gruppe „KPACHODAPCK“ mit dem Künstler Ralf de Moll und dem Improvisationsmusiker Helmut Bieler-Wendt 1982-1990 interdisziplinäre Projekte mit der Malerin und Performancekünstlerin Sibylle Wagner |

Biography

(Excerpt, read more below: “More about Studio SA/JO”)

Sabine Schäfer, 2019,

Photo: Anna-Maria Letsch

|

SABINE SCHÄFER 1957 born in Karlsruhe, Germany. Lives and works as media artist and composer in Karlsruhe. From 1997-2013, acting as artist-couple, together with Joachim Krebs. Since 2014, beyond the veil of Joachim Krebs, the Studio <SA/JO> is continued by Sabine Schäfer |

|

ARTISTIC PRODUCTION Since 2017, Development of interactive grafic reproductions with Audio QR Codes |

|

VOLUNTEERISM Since 2018 Member of the board of the Section Media Art and Photography of the GEDOK Karlsruhe |

|

EDUCATION / TEACHING Studied piano and composition at the University of Music Karlsruhe: composition with Mathias Spahlinger and Wolfgang Rihm / master’s degree in 1992, improvisation “Gruppe Kreative Musik” with Eugen Werner Velte, piano with Günter Reinhold 1989 1987/88 Since 1989 2015 |

|

ARTISTIC DEVELOPMENTS / RESEARCH 2017 2015 1993–1996 1991–1996 1991 1990–1992 1991 TopoPhonien II: first 16-channel, concert sound space installation 1992 Construction of the 24-channel system “Topoph24” for spatial sound control 1992„TopoPhonicZones“: first 16- and 23-channel, enterable sound space bodies 1994/95 Development of a keyboard-controlled MIDI interface for spatial sound control 1999 Till 2002 TopoPhonien – common information: 1989–1992 1988–1989 1988–1989 |

|

PUBLICATIONS ON THE ARTISTIC WORK (selection) 2008 2007 2003 1994/2007 |

|

ARTISTIC WORK AS A COMPOSER-PERFORMER 1987/88 „ULUDAG“ Art-Rock-Projekt u. a. mit Werner Cee (b) und Peter Hollinger (dr) 1984-1991 Gründung der polymedialen Gruppe PANTA RHEI gemeinsam mit dem Komponisten und Violinisten Helmut Bieler-Wendt; zahlreiche Vernissagen-Auftritte, Konzerte sowie die Entwicklung von interdisziplinären Projekten 1983-1986 Konzerte und Performances der Gruppe „KPACHODAPCK“ mit dem Künstler Ralf de Moll und dem Improvisationsmusiker Helmut Bieler-Wendt 1982-1990 interdisziplinäre Projekte mit der Malerin und Performancekünstlerin Sibylle Wagner |

![]() Studio <SA/JO>

Studio <SA/JO>

Studio TopoPhonien

|

(Excerpt, read more via link below: “More about TopoPhonien / studio SA/JO”)

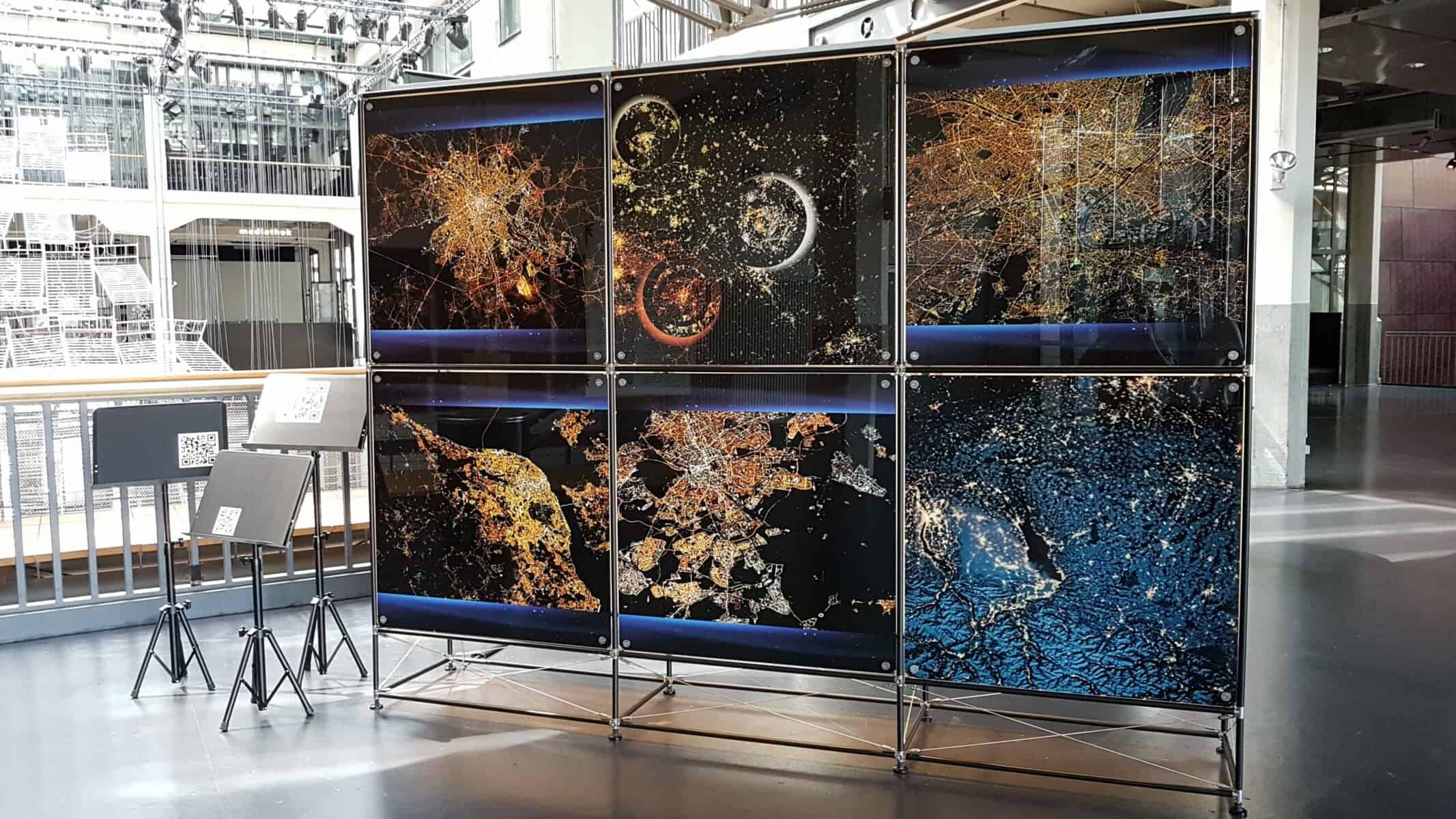

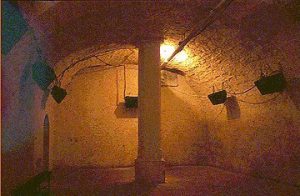

In the context of the series of works “TopoPhonien”, spatial sound installations are created, which are designed and produced on the aesthetic and technical basis of the artistic development project of the same name. The artworks are based on the idea of moving sound, quasi “real”, through a multi-layered loudspeaker body established in the room – by means of a computer-controlled spatial sound distribution system. Thus, spaces individualized by sound are created with walk-in spatial sound bodies, sound sculptures and concert-like spatial sound installations. Sabine Schäfer: artistic idea, composition, production Sukandar Kartadinata: spatial sound control technology (system design), from 1990 Jannis Lehnert: spatial sound control technology, from 2013 |

DATA ABOUT PROJECT DEVELOPMENTS

|

VIDEO DOCUMENTATIONS |

![]() Artist couple <SA/JO> Sabine Schäfer / Joachim Krebs

Artist couple <SA/JO> Sabine Schäfer / Joachim Krebs

![]() Joachim Krebs (1952-2013), composer and media artist

Joachim Krebs (1952-2013), composer and media artist

Lectures

Curatorial

activity

Publications

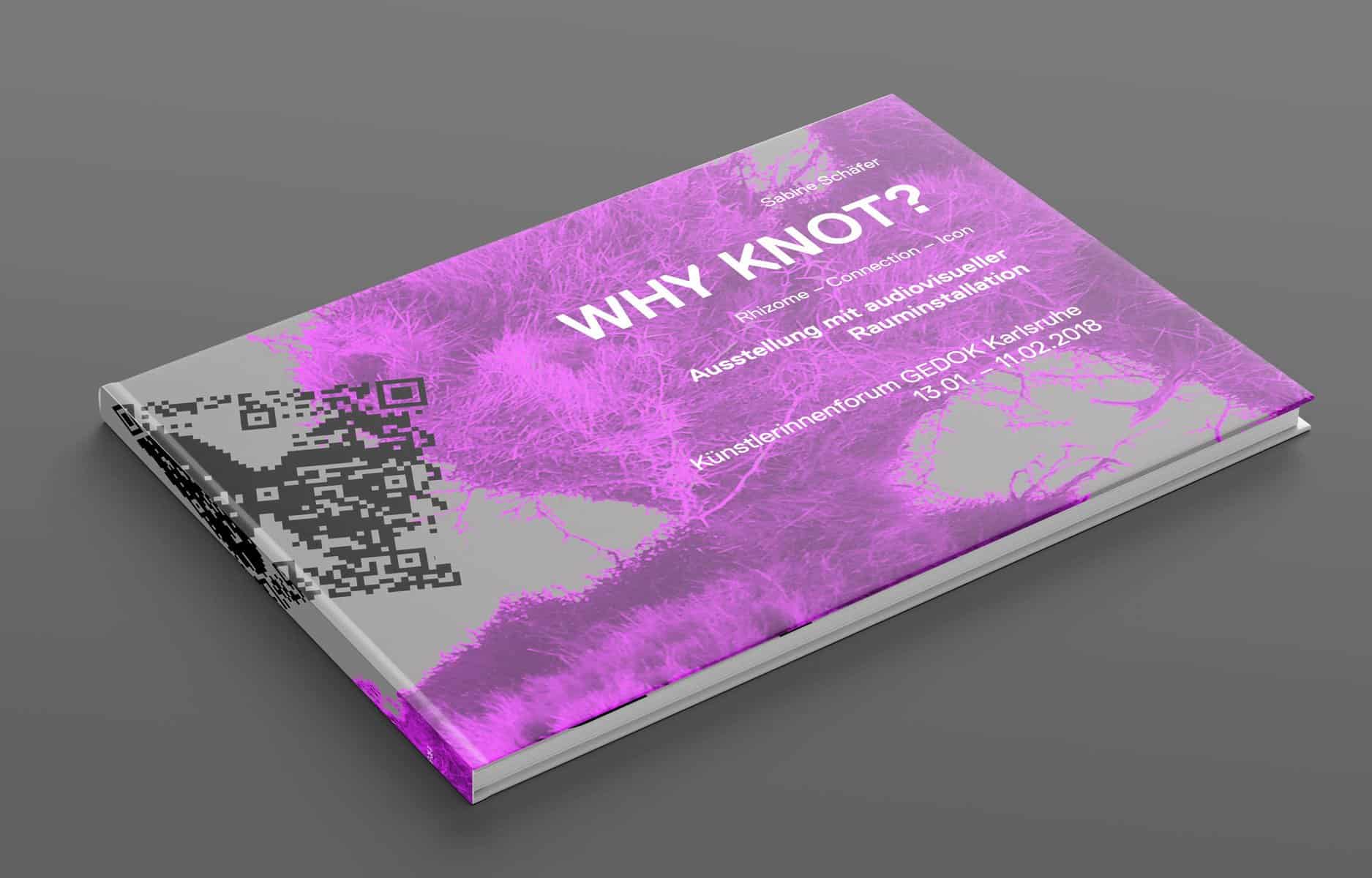

Publication WHY KNOT? Rhizome – Connection – Icon

| Documentation and catalogue about the exhibition of the same name Texts by Dr. Götz Großklaus, Dr. Annette Hünnekens and participating artists More |

|

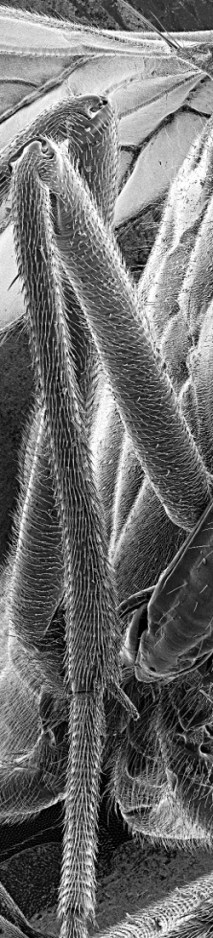

Deleuze and the sampler as AudioMicroscope

|

Release in the context of the book publication: |

Philosophical Reflections on Recorded Music

Middlesex University Press London 2008

<sabine schäfer // joachim krebs>

Deleuze and the sampler as AudioMicroscope

On the music-historical-esthetical and philosophical foundations of the digital, micro-acoustic recording, analysing and production process “EndoSonoScopy”

“The actual musical content of this music

is steeped in ways of becoming woman, becoming child

and becoming animal, but throughout any possible influences

which also depend on the instruments,

it increasingly tends to become molecular,

in a kind of cosmic murmur that makes the inaudible audible

and the imperceptible perceptible as such:

no longer the songbird, but instead the molecule of sound.”

(Deleuze, 1992: 339)

I.

Even as early as during the 1820s, one of the main representatives of the German romantic philosophy of enlightenment, G.W. Friedrich Hegel, stated the following remarkable and „far-reaching“ facts in his lectures on aesthetics: „On certain levels of the consciousness of art and depiction, leaving behind and distorting the natural features is not a sign of inadvertent lack of technical practice or ineptitude, but deliberate modification that is determined by the content, present in conscious thought and required by said content.“ (Hegel, vol. I, 1965: 81). About 100 years later, Walter Benjamin followed those thoughts further in his epochmaking visionary study „The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction“ and remarked that a reproduced work of art „increasingly becomes the reproduction of a work of art designed to be reproducable“ (Benjamin, 1955: 375).

He went on to state that around 1920, the standard of technical reproduction had already succeeded in making the entirety of existing works of art its object, and that it would also have to find its own place among the creative techniques, which process would result in radical changes in the effect that works of art have. (Benjamin, 1955: 366 ff).

From the start, it was thus obvious to the visionary thinkers and artists of the time that those technological inventions and developments that are based on the principles of electricity should not only be „used“ to reproduce already existing works of art, e.g. to accomplish a quantitatively higher output for the commercial exploitation of works of art. Instead, the new technical opportunities should mainly serve a qualitatively intensified production of „tonal works of art“ specifically created for the „electrical“ medium („instrument“) of the loudspeaker. Accordingly, the loudspeaker, for example, would turn into a „mediator“ of music specifically produced for it instead of „just“ remaining an authentic „intermediary“ of vocal and instrumental music.

The rapid developments of the 20th century in the field of the electrical creation of sounds, the recording, broadcasting and communication of music – for example in dance and popular music, in the field of film and video, but also in the area of electronic / electro-acoustical music and computer multimedia art, which the following pages shall focus on – confirm this in many different ways. Electronically created sound as an expansion of the film, the stage, the radio play and of television, but also of the functional field of electric signal tones, e.g. the mobile phone ring tones and acoustic design are omnipresent today. (Similarly to the global Anglo-American pop music – mainly created on electronic instruments – that practically depends in its entire existence on technical media for their communication and mass distribution.)

It follows from this that artificially shaped movement of sound (sound waves) – and what else would the art form of „music“ be in a fundamental physical sense – that are directly and immediately „produced“, e.g. by a singer or instrumentalist, and are not particularly „created“ through a resonating membrane, streaming towards us from loudspeakers have become a rare and „exclusive“ event in our time. The manifold and new correlations and interdependencies between music and technological development and the modified receptive behaviour of new types of listeners, caused e.g. by the independence of space and time, have frequently been the object of research and description. The results include interpretations that are adapted to this kind of listener, by interpreters „playing it safe“, who are more interested in a „faithful rendition“ based on the recognisable similarities to their previously published „interpretations“ the audience is already familiar with instead of taking up a position of a „spontaneous“ and creatively-emphatic role of an „(inter)mediator“ for the work. This essay will primarily focus on the effects of technical progress on the actual process of creating the work of art.

Accordingly, if one is searching for the beginnings and first examples of „acoustical works of art“ (in Benjamin’s sense as briefly described above), in which, for example, the electrical devices for recording are not merely used as a kind of intermediary“ for an acoustical sound report about music(al performances), thus degrading the loudspeakers to instruments used for „musical coverage“ and in which furthermore the „power of nature“ phenomenon of electricity serves to produce the actual artificial sounds, tones and noises, one inevitably meets two kinds of „acoustic art“ in the true range of the „Central European art of music“ that developed roughly at the same time, in addition to the applied forms of art such as the radio play or film music. They are firstly the „electronic music“ as it first developed in Germany, and secondly the „musique concrète“ with its French origins. Both represent the first genuine (and pure) types and forms of music for the loudspeaker as an „instrument“. Since the composers / producers themselves are no longer in need of interpretative mediation for their acoustic works of art, fixed in their form and development through recording devices and on data carrier media, the composer is always simultaneously also the performer and interpreter, as it were, of his own work of audio art. Not only is he able to ascertain the greatest possible extent of authenticity in performance of his work(s) and potentially possible „version(s)“ which he himself recorded in an „ideal“ way, he also gains more flexibility and independence in the availability and distribution of his works of audio art.(1)

It appears to be a fact, too, that the so-called amateur will immediately be able to grasp the „coherence“ of electronically produced sound from a loudspeaker even upon the first hearing, and the force of habit does the rest to create the impression that – in contrast to instrumental sound – the electronically produced sound was „better“ suited to the „electrical“ instrument of the loudspeaker. And is it not strange indeed that e.g. piano music reproduced via a loudspeaker makes the latter sound like a piano, but not look like it, but instead it still looks like a loudspeaker!

Admittedly, the electromagnetic reproduction device will only re-create something that has been „produced“ at an earlier time in any of the cases mentioned above, but it does not „re-produce“ anything that could exist without the former. Instead, it „produces“ the „original“ itself in conjunction with the loudspeakers.

Musique concrète is a special case in this context. Based on the technisised art of noise of „futurism“ by the likes of Marinetti or Russolo from the years 1912/13, Pierre Schaeffer created the „music of noises“ in France from 1948 onwards (he himself referred to it as „musique concrète“ after 1949). Schaeffer took his material of sound and noise, recorded once again with microphones working with electricity, from all kinds of audible matter – in contrast to the electronically created sound material of electronic music. In his collages of sound and noise, e.g. manufactured from everyday noises of any kind, sounds of nature like wind, rain, the rushing of water as well as sounds from animals or humans, he aims for an „immediate“ contact with the sound material without any electrons as intermediaries (Pierre Schaeffer, A la recherche d´une musique concrète, Paris, 1952). For this kind of music, the techniques of manipulation and cut became relevant for the creative production and performance through magnetic tape recording devices in addition to the other „instruments“, namely the microphone and the loudspeakers. Despite the fact that the sound material was not produced electronically, we encounter more than „just“ artificially arranged „reproductions“ of natural sounds and noises, as one might be inclined to assume at first. Instead, we find original and autonomous work of sound art which could only be produced with the help of the „newly“ developed instruments, which in turn could not have been designed and built without appropriate technological developments in this field.

Composers and sound artists have always productively taken advantage of the varied possible interactions and reciprocal relationships between the „individually abstract“, imaginary production of art and the „collectively concrete“, materialised and continually progressive, technically progressing processes (e.g. in instrument making), and they have creatively implemented them – „on the wings“ of their art. New instrumental opportunities of tonal realisation of purely imaginary, „utopian“, (pre)thought sound art repeatedly blessed it with radical leaps in their development. Thus, Robert Moog’s „invention“ and development of the synthesizer from the late 1960s was regarded as a mental, and almost instrumental „accelerator“ for the developments in electronic music.

It would be beyond the scope of this essay, and not appropriate to the occasion if we continued to further examine the aspects of purely electronically created music, particularly because the joint toposonic composition projects of the two artists

The sampler represents, as it were, a circular, closed and thus independent production unit for digital recording, storage, modification and reproduction of („analogue“) sound events of any kind. It would thus have been the ideal instrument for Pierre Schaeffer’s above-mentioned musique concrète. However, Schaeffer had meanwhile in 1958 re-named his „Groupe de Recherches de Musique Concrète“, founded in 1951, to „Groupe de Recherches Musicales“ after he had started to include electronically produced sounds and noises into his works from 1956 onwards. Some therefore held the opinion that the „historic task“ of musique concrète was more or less completed and that its short history spanning one decade should „officially“ be declared as at an end.

We completely disagree with that! For is it not true that here once more the newly constructed, computer aided instruments for the recording, production and re-production of sounds and noises, based on the rapidly progressing digital-technological developments of the 1980s were the ones which were able to provide the necessary innovative impact from the mid-1980s onwards, in order to create, for example, a new acoustic form of art, namely that of a purely auditive art of sound, an art that solely consists of artificially arranged („composed“) natural sounds and noises?

And is it not equally true that through the digitalised process of production and sequence of events, these become in their „innermost“ selves synchronised and artistic-creative elements to be put into a network, since all media and instruments used for the production are based on the same logical, digital functioning principles? (What an extended potential of opportunity!)

Unfortunately, the first developmental years of the sampler as an instrument to be creatively and practically used by the humans to which it was adapted were the last years of the 1980s, and the first of the 1990s, a time when – similar to the previous developmental history of the synthesizer in the early 1970s – it was under the dictates of a commercially optimised exploitation of music through the minimisation of costs during the process of production. Thanks to digitalised access, accurate „to a pixel“, to every parameter of any abstractly possible and concretely available – or those being made available – audio material of the world in all its acoustical dimensions and materialisations, it became possible, for example, to generate so-called „acoustic clones“ of real instruments, which are then used as tonal substitutes for the now obsolete musicians and their instruments. Through the fact of their imaginary presence created through sound „only“ – caused by de facto (visual) absence, since it is only conveyed „indirectly“ through sound/loudspeaker (invisible, but audible (!) existence) – those cheap imitations of real sound arrive at a very deceptive „real“ simulation of „authentic“ instrumental sound. (No more, but no less either!) The „abuse“ of the sampler as a superficial and simplistically ostentatious, pseudo-modern „sound producer“ out for show for the continually available, cost effective use in the computer generated production of short-lived mass-produced articles for video, film and television, exclusively manufactured with commercial aspects in mind, has also become the conventional practice of our time. In the still relatively short history of evolution of digital sampling and technologies of sound processing technologies, spanning barely two decades so far, there is no telling (it is still much guesswork even for a sound artists who thinks and works as a visionary!) which artistic-dynamic-innovative potential for the future of music in general and the art of sound in particular, which is our topic here, is still dormant in the machine-artificial connection of the „instrumental duo“ of sampler/loudspeaker.(2)

The elementary, direct, pixel-exact („particle-exact“) access to the endogenous-acoustic (micro)dimensions of „sound“ as such – be it pre-recorded, „natural“ sounds or electronically produced „artificial sounds“ – that has been hinted at in other contexts and became possible thanks to the digital-technological developments, is owed first and foremost to the universal approach of a generally unspecific sound character of the sampler in the case of complex networking options without hierarchies that are synchronous with respect to „space and time“. In contrast to, e.g. the synthesizer, but also in contrast to traditional musical instruments, the sampler itself does not create its own specific and individually identifiable sounds, timbres and colours. Instead, it first of all reproduces – with all limitations as described above with respect to „faithful rendering of the original” in the image of the reproduced sound of naturally created sounds via „electroacoustical” loudspeakers – the digitally recorded, analogue sound event that was previously recorded in the „traditional“ way with the help of a microphone, preferably 1:1 (a so-called „machine to reproduce recordings“!) In the process of „digital recordings“ where an analogue signal is transformed into a „digital signal“, as it were, individual sounds are depicted as numbers, for example in contrast to analogue forms of recordings, and are recorded as numerical codes. The result is more than a „linear“ and less distorted tonal image, and thus a „higher“ quality of reproduction: the digitally stored sound materials are now – at first apparently unlimited, when human categories of thought are applied – prepared for a highly differentiated creative further modification. Unlike traditional tape technologies, those artistic options of access and production are hugely extended, and even amateurs immediately suspect and understand the (quality enhancing) dimensions, e.g. when they compare the options for later modifications of their older, analogue photographs with those modern digital image editing programmes that can easily be realised nowadays with any PC and appropriate software.

Not later than the 1990s, digital image modification and computer generating technologies had become the standard in international, usually commercially oriented, professional video, film and TV productions. However, there are comparatively few artistic examples in the field of „pure“ art music that artistically adequately utilise the innovative-technological and, in particular, „utopian“-creative opportunities for the development of synergies between the production unit, „sampler“, and the instrument of mediation, „loudspeaker“. And thus, the sampler, still in its simplest form and with little storage space, when it was at all used from the mid-1980s onwards, was used rather sporadically, and mainly in live-electronic, experimental jazz and improvisational music and in the multi-media networked performance and action art scenes.(3)

Not least in the course of a forced technological development in storage chip manufacturing and the accompanying huge extension of storage capacities and possibilities of production, musician, composer and sound scape artist Joachim Krebs had managed from the mid-1990s onwards (in the first years mainly in his electro-acoustical sound art project „Artificial Soundscapes“) to develop and formulate an extremely extended and therefore radically modified tonally artistic and music aesthetic approach to electro-acoustical sound art – both in theory and in practice, and based on the now fully fledged and highly evolved technology of sampling.

In order to immediately counter any misunderstanding that might arise: of course we are not interested in an uncritical, purely affirmative relationship with technological development as such. And we have no intention of taking sides for a solely mechanistically motivated, continually „improved“ and, with respect to the definite, negative global effects that (also) occur, loyal progressive definition of development which today, in the 21st century must needs appear to be „puerile“; and much less advocate the thesis that „new“ music would almost automatically be generated through new technologies or new instruments. Quite the reverse: on the one hand, it took years of practice and experience with the artistic use of the sampler (since 1985) in many live concerts and studio productions, and on the other hand, an intellectual and theoretic background and foundation in the form of the philosophical writings and „multi-route“ thought structures of the great and visionary French thinker Gilles Deleuze to allow the development of a „pure“ tonal art in the direct musical tradition of, e.g. the Italian futurists from the era around 1910, the Dadaistic phonetic sound poetry of the 1920s, the tape sound/noise collages of the French musique concrète and the electro-acoustical compositions of, e.g. Luc Ferrari and Iannis Xenakis. A purely „acoustic art“ that especially places the sensation of the exclusive process of listening at the centre. All this with the smallest visual performance share and multi-media character of an installation, and finally combined and composed from natural sound and noise materials recorded and modified with the sampler.

II.

Whereas the previous remarks were rather more in a vein of historical philosophical, musical technological and music sociological thought, and while the relationship of „autonomous“ productions of art and of technical progress, especially with respect to the radically innovative options for the recording, production and reproduction of digital sampling technology was at the centre of attention of this essay so far, the following pages are mainly devoted to those briefly mentioned philosophical and theoretical basics that, among other reasons, were behind that original development of the „EndoSonoScope“ process (interior sound representation) which shall be described in the following.

It was in 1920 when Paul Klee (one of the indubitably most important artists of the recently ended 20th century) among other things first formulated that momentous principle which was to become so famous about his quest, originally regarded as „puerile“, for another („true“) reality that must be hidden behind the appearance of things that we are accustomed to: „Art does not reflect what is visible, it makes things visible.“ (Creative Confession, 1920). With this statement, Klee not only pointed out that defect we initially described in another context, namely that the production of art – whether with or without the use of technology – would fall far too short if it stopped at only the purely illustrative reproduction of surfaces and superficial appearances of nature or matter, and would attempt to unnecessarily doubly imitate only those which could also exist without art (or technology), which will furthermore never be quite the same as the original! Instead, he first of all intended to point out the process-like and immanent movement during the actual creatively designed „process of making visible“ itself, in addition to the second aspect of „making visible“ the previously „invisible“ that is mentioned (and that should not be imagined as a cheap magician’s trick).

The main concern here is therefore the depiction of dynamic „ways of becoming“ (Deleuze), not the static condition of „being“. For example, one should not reproduce the flower, but the „blossoming“ (4), not the river, but the „flowing“, not the dog, but the „barking“ (5)5, etc. At the same time, the following statement by Paul Klee also contains an important „utopian spark” (Ernst Bloch): „Furthermore, I do not wish to render the human being as it is, but only as it could also [!] be.“ (Form- und Gestaltungslehre [Principles of Form and Creation], vol. 1: Das Bildnerische Denken [The Thinking Eye]).

Gilles Deleuze, in whose writings Paul Klee appears in very varied contexts, for example wrote in „A Thousand Plateaus“: „… and then, when he [P. Klee] had made himself comfortable „within the limitations of the world“, was interested in the microscopic, in crystals, molecules, atoms and particles, not in scientific exactness, but in movement, only in the inherent movement; …“ Deleuze, 1992: 460). This passage makes it very clear that this is not only about things that are „concealed“ or another reality behind matter, but instead about (concretely, as it were!) concealed objects directly from the micro-dimensions of the „interior“ and about the dynamic process of setting free some inherent, hitherto „unthinkable powers“ and the „alienation/exterioralisation of inner intensities“.(6)

From one’s own (interior) middle, ever more extensive and consistent materials are to develop in a self-dynamical and self-intensifying manner. These in turn release ever more intensive powers and energy or create them in the first place. The continuing varied generation of matter therefore turns to an active, „synergetic symbiotic“ and direct relationship of material and power instead of solidifying in a formal, static-mechanistically separated, pseudo-dialectical „contrast of dichotomy“ – here: matter, there: form. „Today, it is important“, as Deleuze continues, „to use the material that can monopolise the powers of another order…“ (Deleuze, 1992: 467)

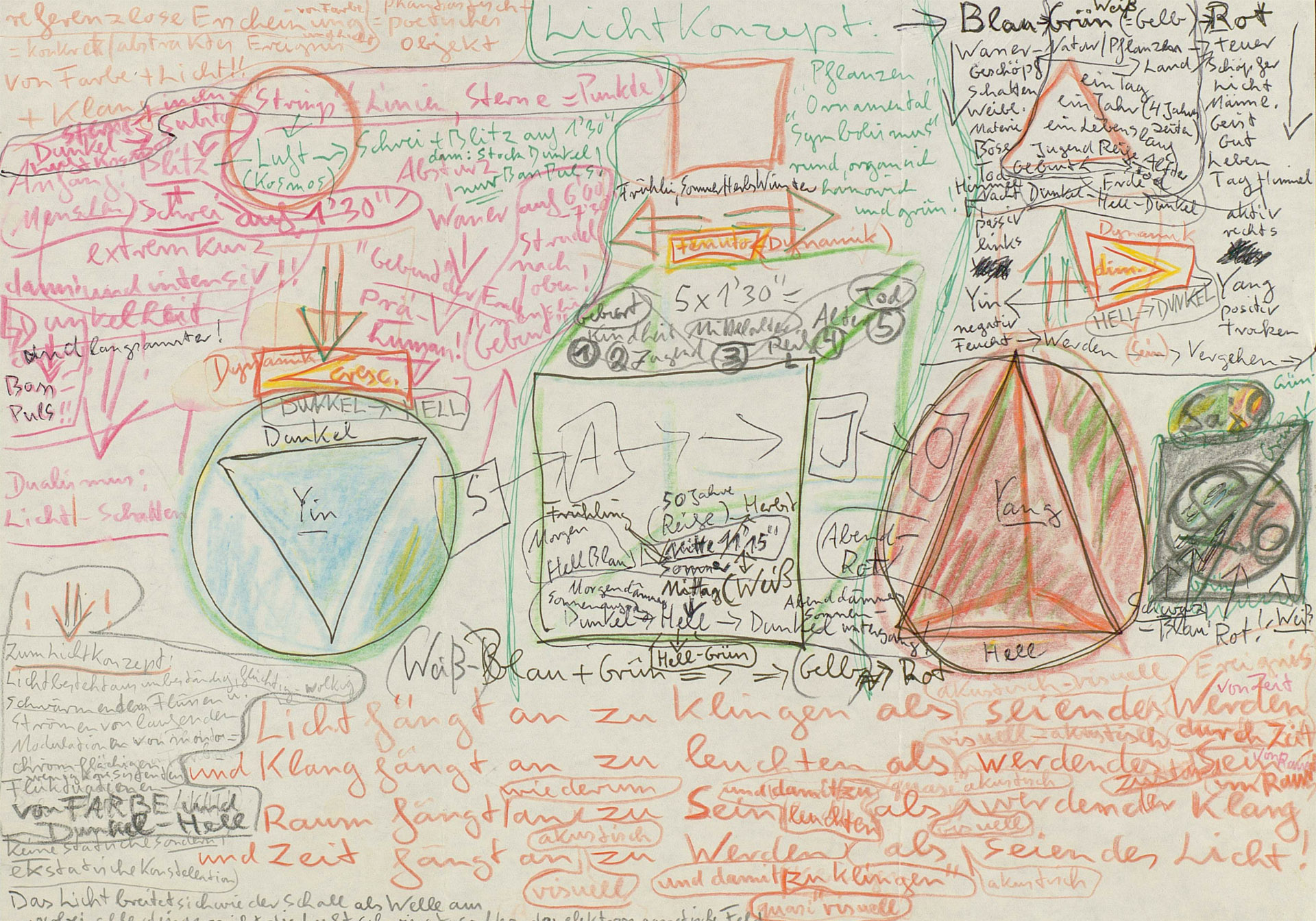

What might all of this mean for the physical medium of “artificially moved air” and thus, in the broadest sense, for the art of music which per se represents itself as an „acoustic art of time / art of the times“, temporal dynamic, and especially characterised by and in the flow of time in a linear direction? Deleuze, who repeatedly describes the manifold kinds of relationships between his philosophical thoughts and the medium of sound in his writings, elaborates on the following in his chapter „1837 – On the Ritornello“ from „A Thousand Plateaus“: „Music molecularises the matter of sound and can therefore capture inaudible powers such as duration or intensity. It can give a sound to duration.“(Deleuze, 1992: 468) „The molecular material itself is so de-territorialised that it is impossible to refer to material of expression, as in Romanticist territoriality. The materials of expression cede their place to a material of collection or monopolisation. And the powers to be monopolised are no longer powers of the earth, still constituting a large expressive form, but instead they today are powers of an energetic, shapeless and immaterial cosmos. … The post-Romanticist turning point was that the essential was no longer contained in the forms, materials or topics, but in the powers, in the density and intensity.“(Deleuze, 1992: 467) And in the context of compositional processes as employed by French-American composer Edgar Varèse, he wrote about a „musical machine of consistency, a sound machine (not intended for the reproduction of sounds) that molecularises the tonal material, atomises and ionises it and captures a cosmic energy. If this machine is yet to have a structure, then this must be the synthesizer. By combining the modules, original and editing elements, uniting the oscillators, generators and transformers and combining the micro-intervals, it makes the process of sound and the production of this process itself audible.“ (Deleuze, 1992: 468)

Deleuze wrote this in the 1970s. And as we described above, this was the first decade of the synthesizer’s development. The (digital) era of the sampler which did not come until the mid-1980s had of course not arrived yet. And still, how accurate Deleuze’s statements – e.g. concerning the synthesizer – were with respect to the instrument of the sampler which was, naturally, completely unknown to him at the time, was something we quickly discovered during the late 1990s when we were working on developing of the „EndoSonoScope“ process. This specially designed micro-acoustic procedure for the recording and analysis of the largely unexplored and unknown („interior“) micro-dimensions of „naturally“ created sounds and noises employs the sampler in the original, specific way, almost exclusively as a so-called „audio microscope“.

The term of a musical machine of sound and consistency, one that „molecularises the matter of sound“, surely also anticipated by Deleuze in a metaphorical, even „metamorphic“ sense, and related to purely electronically created „sound matter“ when meant in a concrete and practical way, is first of all realised here in a „real and practical“ manner, and extended by the crucial aspect of the extension of the term matter to mean „everything that sounds in this world“, without limitations to „self-produced“ sound matter, usually electronically created by humans or with the help of an instrument. Since the sampler accordingly exclusively generates the sound material that is to be reproduced later on from previously digitally recorded acoustic „alien“ materials – and does not, like traditional instruments (this of course includes the synthesizer), create them itself – it is able to enter the omnipresent „organic texture of sound“ in its capacity as an ideal and central „machine of sound molecularisation“ with a complex of computer-aided interfaces to „molecularise“ the fragment samples (samples) taken from it – at least in acoustic terms. The sampler functions as a „high-performance audio microscope“ in this context, which not only makes the „inaudible“ audible in addition to digitally representing the „interior sound“ (EndoSonoScope) and molecularising of the sound, but first and foremost prepares, even enables both the natural creation of consistency and the one the sound artists must produce artificially by „rendering“ the process of the sound production itself „audible! Artificially creating the interdependent and naturally-artificially produced consistencies as a permanent, dynamically fluctuating process of continued variation – between the „concrete“ and the „abstract“ – is the prerequisite for evoking those unknown „interior“ acoustical intensities and temporal permanences. In their turn, they give evidence of the existence of a „imaginary-auditive landscape and vegetation“, one that „lives and thrives“ underneath the acoustical surface, as it were. The acoustically imagined habitat as an „audio-sphere“ for multifarious „audio-mutations“ and new acoustically oscillating types of „being and vanishing“ – symbiotic between „concrete naturalness“ and „abstract artificiality“.

It stands to reason that the basic audio materials for the creation of our ToposonicCompositions should be taken from the natural spheres, and especially from the animal world. And indeed, we received clear confirmation of the widespread scepticism many people display for example towards electronically produced sounds as „synthetically dead material“ even in our first trials with sound microscoping. For example, if you compare the „interior“ richness of a grasshopper’s „song“, „arisen“ in millions of years and developed in a highly differentiated way, for the first time made audible by the process of sound microscoping, with the comparatively undifferentiated sound signal of an electronic sound generator or something similar which sounds monotonous and „lifeless“, then the lack of sound materials that evoke „inaudible-hidden“ and “unthinkable powers“ becomes very obvious (clearly audible!), especially in the sound-microscoped, acoustical micro levels of electronically produced sounds and noises. For the great chance of „evoking“ those powers (at least acoustically) that are „unthinkable“ for humans is not to use any sound material for the creation of the audio works of art that were „thought (up)“ and produced by a human being, but instead immediately to return to the almost „desubjectivised materials of expression“ of the many („sound-microscoped“) animal sounds and natural noises – that are beyond any human imagination and productive powers. The share of the production that is designed „subjectively human“ should then mainly be limited to the artistically-creative selection (What?) and artificial combination (When, Where and Who with Whom / Which with Which?) of the previously molecularised and meticulously analysed and catalogued sound materials.

Another important advantage of utilising only the recordings of „naturally“ created sounds and noises from the three basic categories of natural resources for material: „animal“, „nature“ and „human“ – especially for generally conveying and receiving our toposonic art – is the universal character of the sounds and noises of natural origin, familiar to everyone on an everyday basis. This universal character allows many people spontaneous access to the actual ToposonicComposition, despite the „experimental“ and avant-garde aesthetic basic approach in all our toposonic works of art, without certain, („nationally“) marked, socio-cultural previous experience, let alone special expert knowledge that is often indispensable for an adequate reception of „euro-centrically“ shaped new („classical“) music.(7)

But what does one do now with all those sound materials one has selected, audio-microscoped, analysed, and catalogued according to artistic criteria (and which first appear to be rather foggy and chaotic for human ears and minds) in order to artificially elementarise them and put them to proper use in a potential ability of consistency – permanently hovering between an already existing, „naturally-concrete“ and „artificially-abstract“ fluctuation that must be artificially produced? Deleuze wrote on this subject: „It may well be that one does too much, puts in too much and works with a mess of lines or tones. And instead of producing a cosmic machine that „lends a sound to something“, one falls back on a reproductive machine which eventually only reproduces a scrawl that deletes all the lines, a mess that jumbles all the sounds. One pretends to open the music for all events and influences, but what you eventually reproduce is a jumbled mess that prevents any event. All that is left is a sound box that creates a black hole.“(Deleuze, 1992: 469).

The material must be sufficiently de-territorialised for it to be molecularised and to open itself for the cosmic element instead of retreating into static accumulation. This condition can only be realised through a certain simplicity of the non-uniform material: the highest possible degree of calculated simplicity in relationship to the disparate elements or the parameters (Deleuze, 1992: 469/470).

Following the molecularisation of sound material, and the accompanying process of making audible / „making thinkable“ the inaudible and unthinkable powers to be captured, which in turn served for the acoustic evocation of (inaudibly) concealed „interior intensities“, the compositional processes of „auditive elementarisation“ and „artificial creation of consistency“ gain increasing importance in order to even artificially create well-rounded and „organically rampant“, as it were, growing toposonic works of art.

The process of „toposonic elementarisation“ takes place during an artificially initiated production phase of editing „toposonic intensification“. During this phase, the acoustic presence of each individual sound elements itself is noticeably increased through an intensifying creation of transparency by selective partial reinforcement, extenuation or even elimination of individual acoustic parameters values, and furthermore, the previously also recorded specific „acoustic aura (audio ambience)“ surrounding each individual sound component gains noticeable three-dimensional acoustic conciseness in the process of „space microscoping“ (or rather: „acoustic location microscoping“). One only retains the most elementary acoustic presences of the toposonic lines, locations, movements, durations, colours and tempos of the alienated interior acoustic intensities and/or separates them in order to create „natural“ and equally „artificially“ consistent „toposonic environments“ with the help of consistency-creating mixes that continue with momentum of their own, and temporal successive series.

With respect to the question of artificially produced „creation of consistency“ that especially points far beyond natural consistencies, may we add the following remarks as conclusion: Two of the most important requirements for those consistencies that can be artificially „composed“ and are generated in a continually fluctuating „inter-zone“ – between „pure“ concreteness and „pure“ abstraction – are the acoustic processes of deconstruction and transformation. On the one hand, there is the process of the (partial) dissolution of the (non)tonal, sheer concrete „matter of content and meaning“, and on the other, their transformation into a „purely“ tonal but not just abstract, „de-subjectivised matter of expression“, as it were. Both take place in the production process of „toposonic molecularisation“ through „audio microscoping“ and the following „toposonic fragmentarisation“ with a possible „self-intensifying“ creation of loops, as described above in detail. For example, if you start from a small detail, like a picture puzzle, from a „sample (a so-called fragment sample) and are to guess the („whole“) item that is only visually reproduced in fragments, and when the identification of said item is furthermore complicated by enlargements and selective visual depiction of details (in order to make the practically unknown dimensions of the exterior visual form and shape of the items visible), then during the process of toposonic microscoping, the concrete „acoustic matter of content and meaning“, of the „naturally“ created sounds and noises clearly linked to one individual, a natural (physical) phenomenon or a concrete item is turned into a seemingly „different, concrete matter of content“ or frequently „dissolves“ – the smaller you make the „audio fragment“ and the higher you choose the magnification of sound microscoping – into more or less „abstract matter of expression“. „In the mind of each listener, even beyond (extra)musical meanings and contents, in an „inter-zone“, individual, audio-inspired imagination“ is to „unfurl, in permanent fluctuation between (!) „pure“ naturalness and „sheer“ abstraction. This is achieved even more expertly since, e.g. the animal voice, the natural sound or the human voice when singing, is also turned into „something else“: „pure“ line, „pure“ space, „pure“ colour, „pure“ sound, „pure“ rhythm, „pure“ movement, „pure“ becoming, … „pure“ state. … The aim is no longer to develop a form or to force a shape on matter, but to create „ways of becoming“ of alienated internal intensities and de-subjectivised affects. Form(s) should dissolve, e.g. to render the tiniest variations of speed between combined („composed“) locations and fast or slow movements to the state of immobility („silence“) audible.

The artificially created toposonic soundscape created by the ToposonicArtist thus appears to be an ensemble of de-subjectivised matter of expression in a space, time and sound matrix (stacked in all directions) of the „temporally“ horizontal and rhythmically melodic ToposonicFigure and the „spatially“ vertical and resonance harmonic ToposonicStructure (<sabine schäfer // joachim krebs>, 2004: „TopoSonic Spheres“ booklet text contribution for the CD/DVD of the same title).“

Translation by ar.pege translations sprl

References

Benjamin, W. (1955) Das Kunstwerk Im Zeitalter seiner technischen Reproduzierbarkeit, in: Benjamin Schriften,

Bd. I, Frankfurt a. M.: Suhrkamp. 1955

Deleuze, G. and Guattari, F. (1992) Tausend Plateaus. Berlin: Merve Verlag. 1992

Hegel, G.W.F. (1965) Ästhetik, Bd. I, Hrsg. Friedrich Bassenge. Berlin-Weimar 1965

_________________________________________________

1 Incidentally, the fact that the radically modified situation this causes with respect to the possibilities of the production of music often generally seem imperfectly realised, investigated and described in their aesthetic importance and relevance – e.g. by musicological philosophical research. In this new situation, the composer will henceforth be able to fix his completed work of art „authentically“ for posterity „ad infinitum“ – comparable to the man of letters or an artist. He no longer is dependent on the often „problematic help“ from interpreters just to have his work come into existence in a tonal, „materialised“ way! (up)

2 Naturally, there are always the „interfaces“ of the human: a) as a sound artist (sender) and b) as an addressee (recipient). The human (sound artist) as the „sender“ forms a „symbiotic production structure“, as it were, together with the machine (production unit: sampler). And the loudspeaker as an instrument of mediation then forms a so-called „mediation and communication structure“ with the „recipient“ in the form of a „listening human being“. (up)

3 Author Joachim Krebs realised multi-media projects on a larger scale between 1985 and 1994 – for the new art of music and media – at internationally important performance venues where the sampler was used in a „live performance“ (e.g. holiday courses for New Music in Darmstadt in 1988, and the festival „Multimediale“ of the Centre for Art and Media Technology – ZKM Karlsruhe in 1991.) (up)

4 A kind of „becoming a flower“, represented by the process of blossoming. (up)

5 One way of „becoming a dog“ is, for example, represented by the acoustic act of barking. The process of barking is an expression, that is „alienation“ of an inner movement that results in an external movement, among others a movement of the air. The air in turn reaches and enters the ear of the listening human or animal. And thus, artificially formed/deformed air, caused by affects, is transformed into sound in an almost imaginary way! (up)

6 Paul Klee: „For we know that everything would have to pursue the path to the centre of the earth. If one scaled down one’s point of view even more to the microsope level, one once more arrives at the dynamic field, at the egg and the cell.“ (Creative Thought). (up)

7 Gilles Deleuze: „The same is true for both literature and music. The individual does not have primacy, there is only the indivisible unity of something uniquely abstract and of something collectively concrete“. (Deleuze, 1992: 140) (up)

8 If the epistemological statement according to which only the relationship of objects to each other, and not they themselves can be recognised as „those being as such“, and that they are also determined by the position and the perspective of perception of the recogniser, and if Albert Einstein is correct in stating that space, time and mass depend on the condition of movement of the observer and therefore are relative categories, one can say with regard to music, that the „interior conditions of movement“, the inherent affects caused by the music and the „inner emotionalities“ of the listener / recipient, make it possible to experience the observance of „temporal relationships“ of the most diverse relations between speeds – in an almost mentally „qualified“ way. (up)

SOUND – TIME – SPACE – MOVEMENT

Die RaumklangInstallationen des Künstlerpaares von <sabine schäfer // joachim krebs>

Abstract, Introduction, afterword and translation:

Ralf Nuhn and John Dack

Lansdown Centre for Electronic Arts, Middlesex University London

published by “Organised Sound” Vol.8 / 2, Cambridge University Press, January 2004published by “Organised Sound” Vol.8 / 2, Cambridge University Press, January 2004

Abstract

This article describes the theories and practices of the German installation artists and composers Sabine Schäfer and Joachim Krebs. Much of their work concerns site-specific sound installations involving the articulation of time and space. Their principal work methods and materials are described. In addition, they have formulated a typology of five installation types which they describe using their own installations as examples. Each installation type responds to a particular set of aesthetic and practical challenges both for the artists and the visitors. These are discussed and illustrated in the article. The typology extends beyond the specific work of these artists and can be applied to installations in general thus providing a framework for critical analysis. Furthermore, the translators have discussed the issues regarding the specialised vocabulary of the artists and the rendering of such language into English.

Introduction

The term ‘installation’ includes many different types of artwork. Some works are site-specific and derive their meaning from being placed in a specific location with historical, social or environmental associations. Others occupy a space within a gallery or public venue and function in a manner independent of the space itself. In addition to the physical dimensions, structure and position of the installation, the relationship between the aural and visual components is usually of fundamental importance. Both senses can provide mutual support or contradict each other in a series of constantly shifting and occasionally unsettling interactions.

In installations where sound is essential to the work, the sensibilities of musicians can assume a significant role. Working with sound is not, of course, the sole prerogative of musicians. Nevertheless, in general musicians are acutely aware both of the potential of real-world sounds as well as the acoustic properties of spaces. (This is particularly true of practitioners of electroacoustic music).

In recent works of the artist-couple <sabine schäfer // joachim krebs> spaces are ‘sonified’ by means of carefully constructed installations which are placed with meticulous care within the location. The physical arrangement of the loudspeakers becomes in effect a living ‘body’ or ‘organism’ creating a form of mediation between the sound types, their actual movements and the installation situated in the space. The static, physical structure is thereby ‘energised’ by means of computer control via specially designed software and the visitor experiences processes of revealing and exploring spaces by sound.

In the following article <sabine schäfer // joachim krebs> suggest a typology of installation artworks. Each type exemplifies a particular aspect of their practice and reveals a preoccupation for creating the most appropriate installation for the specific space and how it will be experienced by visitors. The value of such an installation-typology results not only from the way it explains the artist-couple’s practice, but also from the more generally applicable criteria it offers other artists. Many installations can be situated within one of the suggested five types. Texts which comment upon and clarify artworks often have a particular authority if written by the artists themselves. Some artists, of course, are reluctant to explain their practice believing the work to be autonomous and capable of speaking for itself. However, when artists are willing to discuss their work, readers have access to the kind of private self-reflection that can be so illuminating.

In translating the article we encountered problems common to all attempts at rendering foreign texts into English. These concern not only issues of selecting the correct English equivalent but also the necessity of communicating accurately the writer’s thoughts. For example, should a translator endeavour to retain the ‘feel’ of the original text? Such a decision might demand the retention of phrases which appear ungainly in English but nonetheless communicate something of the text’s meaning. Many translators of Adorno, for example, seem to adopt this strategy. Sub-clauses are interposed between an introductory phrase and the main clause with its verbs at the end of the sentence. The English translation thus remains defiantly ‘Germanic’ in structure but, far from making the text opaque, the accurate placing of stress is preserved and meaning often enhanced. Alternatively, a ‘free’ approach can be adopted and the immediate comprehension for the reader – both specialist and non-specialist – is given priority. However, clarity can lapse into the simplistic and intelligibility suffers. Our solution is, inevitably perhaps, a compromise.

We have previously translated an article by <sabine schäfer // joachim krebs> describing the work ‘Sonic Lines n’ Rooms’ (SAN Diffusion, Sept. 2000). In this article the artist-couple outlined their approach to the particular problems of this site-specific work (see also: Mitteilungen 33 of DEGEM, July, 1999 and Positionen 37, Berlin, November 1998). It was apparent that two terms required particular attention. The issue stemmed from the way two specific installation-types functioned. On the one hand, a ‘sound-body’ could be situated within a space and visitors are encouraged to approach it from various directions. Or, a ‘sound-body’ could be constructed such that people can move around within its confines. In the former case the visitor is external to the object, in the latter s/he is embraced by it. The German word describing an installation in which the visitor moves around in order to explore the interactions between the space and the sounds is ‘begehbar’. This is the third installation-type, the ‘enterable Space-soundBody’ (begehbarer RaumklangKörper). In our first translation ‘begehbar’ was translated as ‘accessible’ but in the context of the present translation this word seemed imprecise. ‘Accessible’ suggests that the installation comprising the sound-body and the space in which it is situated is available to the visitor if s/he chooses to participate. In the present translation the term ‘enterable’ has been substituted for ‘accessible’. Even though it is a relatively uncommon word, it conveys more accurately the necessity for the visitor to actually enter the installation and actively explore.

By contrast, the German term ‘umgehbar’, used for the second installation-type, indicates that the visitor can walk around rather than within the installation. The term we use is ‘circumambulatory’ as in ‘circumambulatory Space-soundBody’ (umgehbarer RaumklangKörper). This word is almost certain to be more familiar than ‘enterable’ and, as anyone with even a modicum of Latin will realise, it means that the installation can be walked around and approached from any direction (unless deliberately restricted by the artist). Naturally, it would have been gratifying to use words retaining the parallel construction of the German ‘umgehbar/begehbar’. Circumambulatory/intra-ambulatory was considered (albeit briefly) but rejected as too unwieldy. In neither case is there any compulsion for the visitor to walk across the space in a straight line or around the installation in any direction – clockwise or anti-clockwise. Nor is movement meant to be uninterrupted. The visitor should, indeed must, make use of the complete space available to experience the animating effects of the sounds emanating from what appears to be a living ‘sound-body’. The organic metaphor of a “sound-body” is deliberate.

The term ‘Space-soundBody’ (RaumklangKörper) – which must be differentiated from ‘Space-soundObject’ (RaumklangObjekt) – has been retained in English. Consequently, we were persuaded to translate its separate components or ‘Glieder’ as ‘limbs’ to maintain the organic metaphor rather than use the more neutral word ‘parts’.

Lastly, we should not overlook the playful aspect of artists’ language. In the description of their work ‘TopophonicPlateaux’ <sabine schäfer // joachim krebs> use the term ‘Klangfarbgrundierungen’. The play between the words ‘Farbe’ (colour) and ‘Grundierung’ (a painter’s ‘priming coat’) is lost unless the term ‘Klangfarbe’ – literally ‘sound-‘ or tone-colour’ – is understood. However, to express the concept of a first step which is needed before the final application of other sounds, our translation as ‘sound-colour priming coats’ communicates (we hope) the idea accurately (though unfortunately not with the lightness of the original text). Such are the problems of translation and we can only hope we have captured the essence of what these artists wish to express.

I. Time Becomes Space – Space Becomes Time

All modern perception theories are based on the fact that human perceptions of time and space are interdependent. A distance covered by a person – or a sound – in space is initially perceived as a temporal phenomenon, allowing a person to develop a subjective notion of space and time by measurement and comparison.

Thus, movement in space becomes time. Time periods become spatial distances. The sensation of time is realised by the sensation of space and vice-versa. Space becomes an experience of time due to the movement of the sound event. Time accordingly becomes an open, imaginary process of generating illusory space. Rooms which are open, unbounded, liberated from the linearly directed flow of time serve as three dimensional canvases for constantly changing processes generating transitions.

Between TemporalSpaces and SpatialTimes, there are manifold variations of IntermediateZones with their IntermediateSpaces and their IntermediateTimes.

All this leads to a dissolution of the real performing space, where time itself stages a linear-dramatic, goal-directed idea (of space?).

Instead, the cyclic, non-linear consciousness of time releases the desire to become “immersed” in psychological inner space, to fade out physical outer space with its real time and its thinking spaces (which are predetermined in their substance) by concentrating on the perception of what might seem on the surface, unprepossessing sound events based on elementary-harmonic, simple sound-materials and -transformations, to set free your vision, or to put it better, your hearing, so that you may experience the present – from one moment to another – as a possibility of transitions, of freely flowing conditions.

In the Space-soundInstallations of the artist-couple <sabine schäfer//joachim krebs> specific soundspaces are created, which incorporate the movement of sounds in space as an intrinsic part of the composition. The composition’s individual sound strata are, so to speak, transferred into the exterior space and by means of a loudspeaker matrix – which is installed in the space and controlled by computer with software exclusively developed for the artist-couple – moved and placed respectively in space. Hence, the free distribution of sound sources in space and the compositional sound space extended by the real movements of sounds, are specific to this space-sound art. This compositional sound space – primarily defined as time-based art – thus also approaches spatial art. This is comparable with the medium of film/video, in which the image formerly represented statically can, by its movement, be experienced as time-based art.

The experience of space-sound events which are moved in the architechtonic space is not only meant to give an intensive spatial experience, it also becomes an experience of shaping time acoustically and artistically.

Individual sound locations and sound sources are, by their movement, turned into a quasi organically proliferating sound line, which – itself interconnected to build an artificial matrix of time and space – offers acoustic images of SpaceTimeNets floating freely in ‘non-time’.

Space and time themselves are turned into interactive qualities of perception, constantly fluctuating between the ‘real’ and the ‘unreal’ sensation of space and time.

II. Artificial Soundscapes between Pure Realism and Pure Abstraction

In almost all works of the artist-couple from 1995 onwards in the area of Space-soundInstallations, amorphous animal/natural voices and sounds respectively, as well as heterogeneous everyday noises from human surroundings and habitats form the most important sonic source material, though there is neither language, singing nor instrumentally or synthetically generated sound material! Below are examples of the most essential aspects of the artist-couple’s working methods.

An initial, important stage in composition is the intensive study of each individual found and selected noise and sound. The most important question at this stage is: which naturally existing and which potential, artificial consistency is held by each individual sound in the initially inaudible, molecular interior of its microstructure? Therefore, noises and sounds are recorded with a digital sampler. Delving into the smallest molecular region, the sampler is able to put at the disposal of the sound artist single particles of the inner structure of this noise-sound matter for artistic development. With these ‘abstract machines’ – to quote a concept of the French philosophers Deleuze/Guattari – we carried out, as it were, what we called an ‘EndoSonoScopy’ of the individual sound materials to take single sound tests (so-called samples or fragment-patterns) from the organic sound web. Here the samplers serve as audio-microscopes with a complex of interfaces, which enter the organic sound structure in order to record and split their variations into molecules. These are then artistically transformed in a further operation.

Previously imperceptible inner-polyphonies and harmonic sound-fields of unfolding inner resonance spaces now become audible. What occurs is, as it were, a revealing and exteriorising of the inner intensities of the respective sounds.

All of this was ‘preparatory’ work carried out according to a quasi scientific approach of the observer and researcher; only now does it become interesting for the actual artistic composition process. The next stage is to produce an artificial consistency by means of the most varied artificial transformations of the previously carefully selected sound materials.

The artificial consistency formation as a symbiotically-fluorescing ‘animal-nature-noise- becoming’ of sound succeeds here all the more when the animal, nature, noise becomes something ‘other’: pure line, pure colour, pure rhythm, pure movement, pure figure… pure condition.

Furthermore, so-called ‘artificial sound milieux’ are formed in a quasi acoustic amalgamation process. That is, a temporarily existing, specific mixture of sound substances and particles creates a symbiotic diversity of dynamically driven SoundEnergyStructures by means of self-impelled, proliferating self-intensifying loops – always starting from the middle (mi/middle lieu/place).

Another essential aspect of this microscopy of sound and noise is the dissolving of each particular sound’s semantic meaning. Whereas, at its original pitch, the sound was identifiable as something ‘definite’, for example a frog or a toad, it moves further away from its original semantic character the stronger the augmentation degree is. One could also say that the subjective substantial matter of the original sound transforms into a desubjectivised expressive matter of transformed fragment patterns. Intermediary stages during changing consistencies are formed, between concrete and abstract, natural and artificial and so on.

Thus, the artificial soundscape appears as an ensemble of desubjectivised expressive matter in the artistically layered sound system of the horizontal, rhythmic-melodic sound figure and the vertical, resonant-harmonic sound-space.

III. The five most important types of Space-soundInstallations

Over several years different types of Space-soundInstallations have crystallised and developed – due to, amongst other things, different performance situations. The five most important types will be illustrated below:

- The Space-soundObject

- The circumambulatory Space-soundBody

- The enterable Space-soundBody

- Space-within-Space

- Concert Space-soundBody

Afterword

by Ralf Nuhn and John Dack

There is, of course, no compulsion for artists ever to write about their practice. The histories of all the arts have bodies of artworks with little or no corroborating evidence from those who produced them. The theory is there, of course, but it is in the work and we must disentangle it if we choose to analyse the work. However, since the beginning of the last century and the institutionalisation of art there has been a marked increase in texts written by practising artists who want to (or feel obliged to) communicate the processes and underlying aesthetics of their work. These might be texts written to emphasise a personal role in an art-form’s historical development – how many claim to have “invented” minimalism or conceptual art, for example? Other authors are deliberately polemical such as the young Boulez condemning as “useless” all those who failed to recognise the necessity of serialism. Some, due to their role as teachers theorise their practice within a pedagogical framework. For the theoretician or critic all these writings provide valuable source material. Any form of self reflection will almost certainly be appropriated by the academic community as an invaluable research resource. It is an important way in which intellectual and aesthetic discourses are created and sustained.

The sound installation categories of <sabine schäfer // joachim krebs> described in the article have been developed in the context of their own unique and original practice. The absence of references to other artists indicates neither unfamiliarity with the world of installation art, nor excessive introspection. As artists who write about their work, their principal responsibility in this article is to provide a coherent account of their own practice. Our role as translators is to render the text accurately into English. However, due to our close contact with the text and its authors, a secondary contextualising role has emerged. Once a typology has been suggested it is available to everyone and can be used with or without modifications to see if additional works can be included within its categories. Some will be placed easily, others will resist inclusion. Both results can be informative.

For example, the circumambulatory Space-soundBody (category 2) is, broadly speaking, identical to sound sculptures in general. Both terms refer to a three-dimensional object which can be walked around and which emits sounds in different directions. One could, therefore, place sound sculptures such as Stephan von Huene’s Extended Schwitters (1987), Trimpin’s Liquid Percussion (1991) and Rolf Julius’ Zwei Steine (1999) in this category.

However, a clear distinction must be made. <sabine schäfer // joachim krebs> emphasise that, due to the use of multi-channel recordings and individual loudspeakers, the limbs of their Space-soundBody can emit different sounds. This use of specific sounds from each limb would differentiate their works from those cited (with the possible exception of Trimpin’s Liquid Percussion). Nevertheless, this does not contradict the initial classification. The consideration of the specific role of sounds simply adds a further stage of refinement.

The first category – the Space-soundObject – can also be applied in this way. In this two-dimensional arrangement, sound is emitted in one direction. Similar examples are Takehisa Kosugi’s Interspersions (1987) and Christina Kubisch’s The True and the False (1992). In both these works small speakers are mounted on walls in plant-like configurations with the loudspeaker wires resembling stalks. The distinct character of each work depends, naturally, on the specific lighting, the position within the venue, the object’s dimensions and (most importantly) the sounds used by the artists. By including these works in the category of Space-soundObject these individual features are not disregarded. The defining aspect of the category is still the directionality of the speakers and the restriction placed on the viewer’s position. Additional examples can be suggested for the other categories.

As the enterable Space-soundBody (category 3) has loudspeakers placed on the walls of the space at various heights and positions, the visitor can move freely in order to experience different auditory perspectives. An obvious historical example would be the Philips Pavilion at the Brussel’s World Fair in 1958. Though in this case the movement of the sounds and the accompanying images were more important than the “sonification” of the space as such. Other examples are Bernhard Leitner’s Ton-Raum (1984) and Ryoji Ikeda’s A (2000). In the latter case pure sinewaves and random noises were played within a narrow, purpose-built corridor. The acoustic properties of this, albeit simple, space created different listening experiences for the visitors. By walking at different speeds and by changing direction along the corridor, the visitor could locate and pass through distinct “sound areas”.

Examples of the fourth category – Space-within-Space – are less common. This type is based on a self-contained enterable Space-soundBody within the confines of a gallery or a similar space. Consequently, such a Space-soundBody is also circumambulatory. Once again, a potential example can be found in the works of Bernhard Leitner. His Cylindre Sonore (1987) is a cylindrical space containing 24 loudspeakers. The sounds emitted are modified by natural factors such as temperature, humidity and light. Our sole reservation regarding this work as Space-within-Space is that is it situated in the open air rather than within a venue with clear, architecturally defined acoustic characteristics. However, the visitor to Leitner’s space will experience both the sounds within the cylinder and the sounds from outside.

Finally, the five criteria of the final category – the concert Space-soundBody – conform to certain electroacoustic compositions where live instrumentalists play in conjunction with recorded sounds. Even though an exploration of the specific characteristics of the venue is not the principal objective, the practice of sound diffusion is necessarily influenced by the venue’s acoustics. No electroacoustic composer would minimise the importance of this relationship which will, therefore, have a decisive effect on the work as a whole. For example, Stockhausen’s Kontakte für elektronische Klänge, Klavier und Schlagzeug (1959-60) has a fixed form and audience-instrumentalist relationship. In addition, the use of four channel tape and the positioning of the loudspeakers and musicians will ensure the intimate connection between the electronic sounds, the live sounds and the concert space.

From these examples it is clear that the typology suggested by <sabine schäfer // joachim krebs> suits some works but needs modification for others. It must be stressed that this particular typology was the end result of the work and practice of <sabine schäfer // joachim krebs>. This is its unique quality and its strength. Had it been developed by a theoretician, musicologist or art historian the problematic nature of several of the aforementioned examples might well have been addressed by creating sub-categories. However, in our initial attempts the additional refinements usually resulted from considering the types of sounds and how they were used by the artist. This specificity was clarified by an initial categorisation. It is our opinion, therefore, that the origins of these five categories in the works of <sabine schäfer // joachim krebs> does not preclude their general applicability. The art of the sound installation is still relatively new and this typology is an important addition to its theoretical framework.

The Space-soundObject

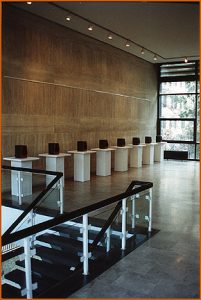

The characteristic aspect of the Space-soundObject is a two-dimensional arrangement of the loudspeakers, which radiate sound in one direction. This results in an optimal reception zone in which the visitor can approach and move away from the object. Therefore, Space-soundObjects are usually positioned against a wall.

Figure 1 shows the Space-soundObject ‘Sonic Lines’, commissioned by Nuova Consonanza, Rome in 1998. The 2-dimensional loudspeaker configuration is placed in the shape of an 8-limbed line alongside a marble wall in the foyer of the Goethe Institute in Rome. The loudspeaker configuration of the Space-soundObject is inspired by the specific dimensions of the architectural space. Clearly perceptible ‘line-sounds’ (forming rolling-ball motifs) are counterpointed by internally fluctuating water sounds which represent the liquid, unstable condition of the 8-channel Space-soundComposition.

Figure 2 shows the Space-soundObject ‘Hörbild’ (‘Audible Picture’). The eleven-limbed speaker ensemble is set into a monochrome, blue sound-wall, resulting in an object resembling an image on a panel. The speaker matrix of the ‘Hörbild’ forms the shape of an infinity symbol.

However, the sound does not only move along the path of the infinite bow, but the speaker tableau becomes instead a territory, a construction for sounds on which they spread, compress, evaporate and become solid again. The Space-soundObject was commissioned by the Siemens Arts Program, Munich and was presented for the first time at the Berliner Festwochen 1995 with the 11-channel Space-soundComposition ‘Tableau I-III’. Further works were produced in 1997 for the first exhibition of the Sender Freies Berlin (SFB) sound gallery and for the MusikTriennale Cologne 1997, commissioned by the Studio Akustische Kunst of the WDR (Klaus Schöning).

Space-within-space

This artistic concept is based on a self-contained enterable Space-soundBody as ‘space within (architectural) space’. Consequently, the enterable Space-soundBody also becomes circumambulatory.

Through the combination of the features of circumambulation and enterability, new qualities emerge which establish an autonomous type of space-sound installation art. An example of this is the Space-soundBody ‘Klangzelt’ (Soundtent) from the project series ‘SonicRooms’ (Fig. 9).

The architechtonic dimensions of the space surrounding the Space-soundBody itself is not explored acoustically – or to put it better ‘sonified’ – a process which would in a sense render the room itself ‘audible’. On the contrary, the installation aims to eliminate as much as possible the real – visual as well as acoustical – environment of the place where the enterable Space-soundBody is installed – it is in fact a room within a room.

The interior of the Space-soundBody entitled ‘Klangzelt’ (‘Sound Tent’) which is easily and effectively separated from its surrounding space by a double fabric cover, leaves aside as much as possible the visual aspect of the artistic design of space and time to intensify the auditory reception of the artificially created virtual SoundSpaces.

As visual contact, a crucial premise for orientation and localization, is prevented by thin draping which is impervious to light but permeable to sound, it is possible to create unreal-imaginary ‘SensorySonicRooms’, where actual moved sounds – perceived only by the ear – can be experienced as an amorphous continuum of fleeting and intangible conditions and acoustic atmospheres.

Paradoxically, the artificial spatial qualities of sound are even enhanced by actual movement. So, in order to experience the ‘Klangzelt’ adequately, you have to be there ‘live’, so that you may, for example, experience the difference between artificially produced spatial qualities in the stereo image and the artificiality of psychological “inner” perception of space, which is evoked by sounds tracing the actual distance from loudspeaker to loudspeaker.

On the other hand, there are artificial ‘listening islands’, which – similar to listening with headphones – shut out the real space of the location by means of surrounding fabric covers, so that the artificially produced spatial qualities of the spatial sound compositions themselves will be more authentically perceived. Thus, at these islands it will also be possible to achieve new listening experiences, which, among other things, may lead to irritations of the ‘normal’ perceptions of space and time. In the best cases the sound artwork evokes a free flowing SpaceTime experience between an imaginary, psychological inner space and an ‘actual’ physical exterior space.

The concert Space-soundBody

The concert Space-soundBody represents a special kind of Space-soundInstallation. The most important criteria of this type of Space-soundInstallation, which focuses solely on sound, are:

- Seating arrangement in the performance space or concert hall (seated audience), resulting in the definitive fixing of the four directions (front/back-left/right).

- Establishing the beginning and end, and thus the total playing time, of the Space-soundComposition with potential dramatic, linearly directed progression of the particular Space-soundComposition.

- Inclusion of a group of instrumentalists as an element with equal rights to the Space-soundBody which would otherwise consist only of loudspeakers.

- The concert loudspeaker-instrumental-body, which is formed from loudspeakers and instrumentalists without any hierarchical structure, generally surrounds the auditorium in a circular- or horseshoe-shape.

- The concert Space-soundBody can be performed once in a concert or there can be several, consecutive performances with the audience admitted at the beginning of each Space-soundComposition.

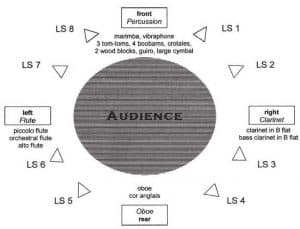

An example is the Space-soundComposition ‘TopoSonic Lines n’Rooms with Instruments’ (from Spring 2002) for a 12-limbed Space-soundBody, experienced in concert form, with 8 loudspeakers and 4 instrumentalists (Percussion, Flute, Clarinet, Oboe).

As a commission for the AUDI-Culture Fund, this work has been tuned especially to the architecture of the ‘museum mobile’ in Ingoldstadt, Germany. To suit the circular performance space the loudspeakers and the instrumentalists, as shown in figure 10, were grouped around the seated audience. By means of a corresponding instrumentation, the instrumental part of the Space-soundComposition – in the same way as the digital 8-channel tape – takes into account aspects of the space-sound movement, resulting in a jointly ‘acting’ 12-limbed Space-soundBody.

The circumambulatory Space-soundBody

The circumambulatory Space-soundBody is a type of Space-soundInstallation the individual exhibits of which have a three dimensional sculptural structure of loudspeakers which can radiate sound in different directions and which is specifically developed for the particular architectural space. The distribution of the sound sources in the space is arranged in such a way that both a horizontal and a vertical linear loudspeaker body are formed, around which one can walk and through which the individual sound strata sound with specifically developed types of movements.

The dimensions, and measurements of the individual loudspeaker-body depend on the size of the performance space. As required, an object is developed for the loudspeaker ensemble on which the loudspeakers are installed, as shown in figures 3 and 4.

As the loudspeakers can radiate in different directions and the loudspeaker ensemble is free-standing in the space, the visitor can – by contrast with the Space-soundObject – perceive the sound from different directions, the term ‘circumambulatory’ primarily refers to the three-dimensional reception mode of the variable listening perspectives, which are of equal quality throughout the entire space.